Lee Aaron: Exclusive Interview for the Metal Hall of Fame

Lee Aaron interview for the Metal Hall of Fame

By Ray Van Horn, Jr.

In 2016, I was writing for Blabbermouth.com and assigned a review of Canadian metal, jazz, blues, and opera legend Lee Aaron’s Fire and Gasoline album. It had been her first recording since her 2004 jazz-pop experiment Beautiful Things (Aaron had already released a full jazz album in 2000, Slick Chick), and it kicked off a six-album new renaissance for her, spanning through 2024’s Tattoo Me.

Aaron was gracious enough to sit with me then for a personal project, dishing a fun dialogue about her Eighties and early 1990s catalog featuring The Lee Aaron Project, Metal Queen, Call of the Wild, Bodyrock, and Some Girls Do while chatting up Fire and Gasoline to supplement my Blabbermouth review.

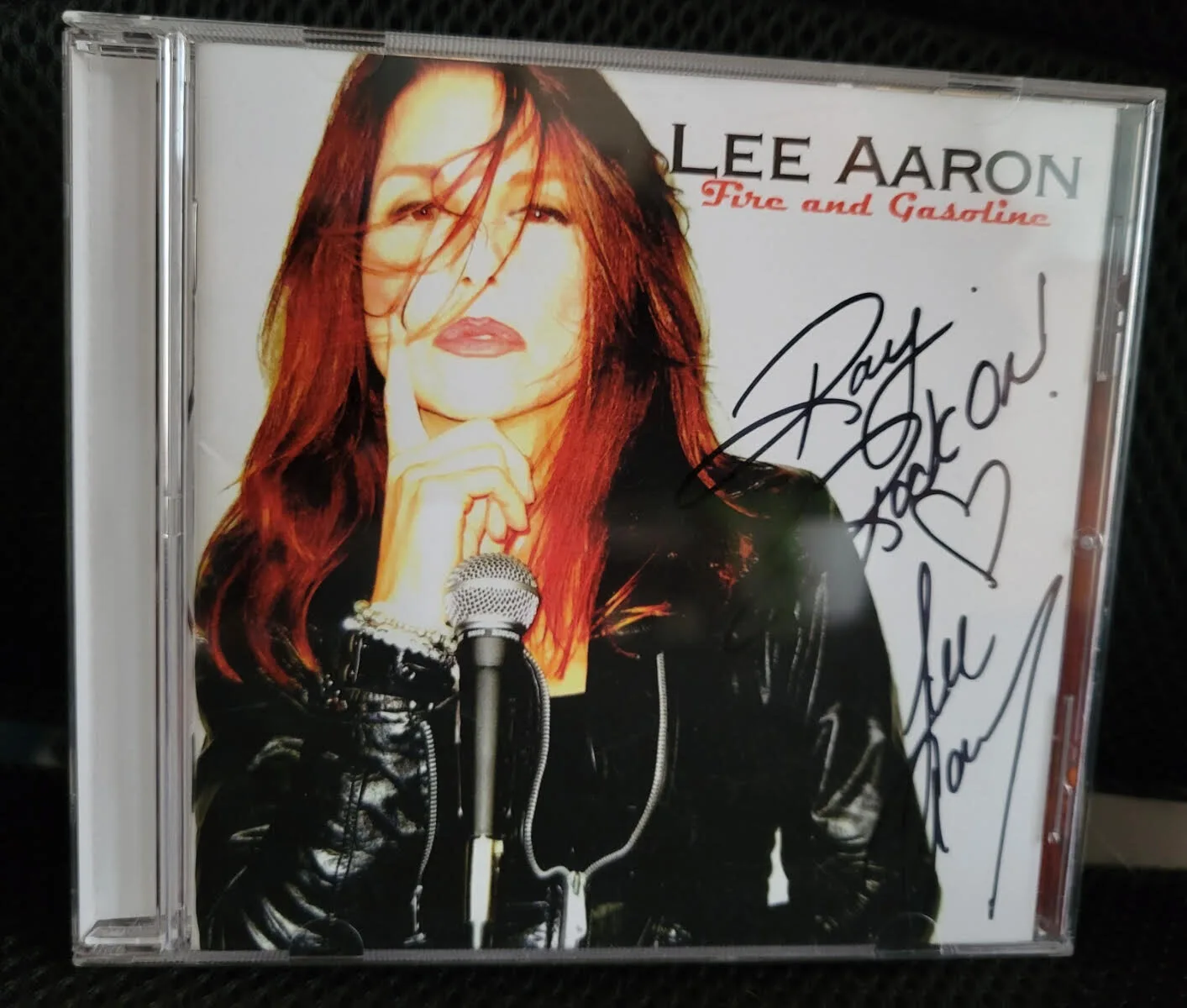

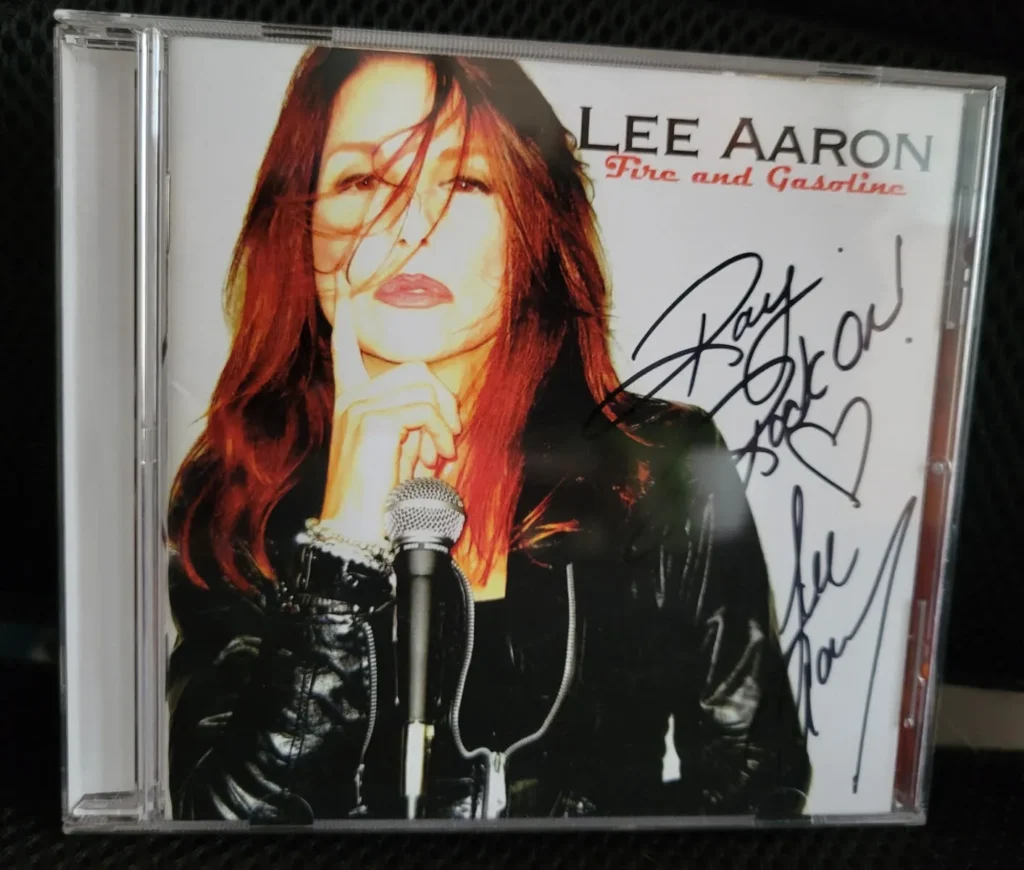

An absolute sweetheart, Lee Aaron sent me a personalized autographed CD of Fire and Gasoline after my review ran. It remains one of my treasures from writing in the scene back in the day. I hope you enjoy this interview footage with Lee for The Metal Hall of Fame.

RAY VAN HORN, JR.: What was that magical album that got you into hard rock and metal?

LEE AARON: You know, it’s funny since I always get asked about my Deserted Island picks, but I would have to say Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti. There are a couple songs on Fire and Gasoline that are more blues-influenced. I’ve really made a connection with that style of rock, so yeah, Physical Graffiti.

RVH: Of all the ladies of metal and hard rock, you were one of the first to gain actual notoriety, yet I feel you and Betsy Bitch got a little sidestepped outside of North America before Lita Ford and Vixen broke out. Do you feel that way and, if so, what might have attributed to this—bad timing, bad management, or bad conditions in the hard rock industry for women?

LA: I know exactly what you’re saying, but unfortunately, we call it the curse of being a Canadian act. Most of the time, Canadians are signed to a larger Canadian label. When I signed my deal with Attic Records, I think I was 19 years old, and I didn’t really understand much about record contracts. A lot of those contracts were designed in a way that you had no control over your foreign licensing. Any distribution partners in other countries had to be negotiated by the label. I had no control over that.

So what often happened was the album not coming out in the States, or some other rhetorical or contractual reasons why—I know in my circumstance—because the owner of Attic Records wanted to start his own imprint independently called Attic America. But he needed “x” amount of dollars and finance, which never ended up happening for him to be able to launch, yet he was holding on to premier acts so he could launch the label down there. So, in the meantime, though I’d have a hit album come and go and there was some interest in the States, I wasn’t able to sign with an American label.

There are various reasons, and again, I’d have a double-platinum album in Canada. At that point in time, Attic was trying to negotiate a label deal for all of its artists. So instead of letting one or two artists go, they wanted the entire roster to be released on a U.S. label. It’s really just political more than anything. I think I really could’ve had a deal in America at that point in time, but I’m not the type of person who harbors resentments or feels bitter about things. It’s water under the bridge; it is what it is. I got to be a rock star in most of the rest of the world! I got to travel all around Europe and Japan, so I’ve had a great life in the Eighties and Nineties doing that. I can’t really complain too much.

The funny thing is, I had a couple of offers in the last couple of years to do a generic rock record with a label called Frontiers, if that makes sense. They’re great and they do great stuff, but I’m trying to say this the nicest way possible: I wasn’t interested in doing a cookie-cutter metal album. There’s lots of that and, honestly, there are people who do it far better than I do. Doro Pesch, she’s great at that; and that’s not really who I am, nor is it who I’m trying to be. I see myself more as an artist in the vein of Heart and the Wilson sisters. It’s definitely more AOR rock—what I do and what I’m best at—so I’m not trying to pretend to be something that I’m not.

RVH: Looking at early live footage, it seemed like you were having so much fun. Crazy having wardrobe changes right onstage behind the screen. Nobody would have the stones to do that now! Put me there from your perspective in the early Eighties, and what were the crowds like as you were coming up—receptive or skeptical?

LA: All three! I guess it all depends on who you talk to, right? That silk-screen thing got dropped fairly quickly. My first manager, it was basically his idea. For me, it was like Alice Cooper, this persona. It was supposed to be all campy and Vaudeville, but very quickly, people went crazy and it got completely twisted around and sexualized in a lot of the press. I realized quickly that if I wanted to be taken seriously as a musician, I had to scrap that thing!

RVH: Tell me about shooting the “Metal Queen” video. Part of that looked like a freaking scream to do, but then there’s the fire sequence, which had to be way too close for comfort! The monk set on fire, I mean, total chaos! Nobody would go to those levels anymore to shoot a music video!

LA: Probably not, but we did a lot of crazy stuff back then. It was all in good fun. All of those fire sequences were done with a fire marshal on site, and there were guys who were specialized in knowing how to do that kind of thing. When my arm was set on fire, I had this sort of barbarian sheepskin wrap kind of thing. I think there was a wet towel underneath, and whatever the type of fluid that they put on it, it was fast-burning. It didn’t get hot and it didn’t touch my skin, and everybody was standing nearby with fire extinguishers, so it was all done quite safely.

RVH: You managed to keep your finger on the pulse of where the trends in hard rock were going throughout the Eighties—i.e., power metal on the first few albums, some power pop on the self-titled album, blues and party metal in the last part of the decade. Do you feel you made all the right moves and, if so, do you feel you were appropriately respected or ignored?

LA: I would say both! It’s interesting you say that. I don’t have any artistic regrets. I did one album in the Nineties and it was hooked up with Sons of Freedom. They were like Nirvana in that sort of vein, and they loved my voice! There was definitely more alt-rock than anything I’d done in the past, but I’ve been somewhat experimental. You know, I actually loved grunge when it happened! I was a huge fan of Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana, so experimenting a little bit and having my music slightly leaning in that sort of direction, I didn’t think there was anything wrong with it. The Rolling Stones have traditionally experimented their entire career, but it still sounded like them, and I think the continuity is there. Obviously, my melodic writing style and my voice are still there.

That album with Sons of Freedom—I did an album called 2preciious—and it was a complete commercial failure! I’m really proud of that record, though! I still think there was some really cool songwriting that I did and, for whatever reason—timing, the label, whatever—the fact was, in the Nineties, people were attached to corporate rock in a way I couldn’t get invested. The trends had changed, so to speak.

As you say, music is cyclical, but I had the great experience last year playing a big rock show in Toronto. I had a few guys fly over from the UK, and these guys were university professors! They were like, “Lee, we came to see you because our favorite album is that 2preciious record.” I’m like, “Oh, man, you just made my night!” They really appreciated the writing, but the album never really had a chance to have a kick at the can. So I’ve had some interesting things in my career. Part of the reason I took a complete diversion and sang blues for a while is I was getting a little tired of being completely pigeonholed as this sword-wielding, foul-mouthed party-girl metal queen. I guess the image was bigger than life, right?

So I thought, “Screw you all! I’m going to do something completely different!” Sincerely, my motivations throughout my career weren’t financial. When I was trying to be a rock star, I was trying to do things that paid myself logistically. The nice thing is I got a lot of great reviews when I started doing jazz, and it certainly changed people’s perceptions that I was definitely an artist capable of stepping outside my box and doing other things, much like what Lady Gaga is doing with Tony Bennett right now.

RVH: Do you feel doing music videos during the rise of MTV was a benefit to you or a necessary evil? It looks like a lot of top-notch production went into your promo clips, especially during the late Eighties and early Nineties where you and the band look like you all were having one big party after another on camera. The swinging tire for “Some Girls Do” looked like a blast.

LA: I grew up in the era of MTV, so I loved video, and I still love video. I think vision is important to help your music come to life. Setting pictures to music can help people understand the motivations behind the music better, so I’m a big believer in that. A lot of those videos from the 1980s, I wanted people to understand that I had come out of the era of fire and brimstone, and I wanted to be having fun and I wanted the rock to be fun. You look back and you watch those old Beatles movies; they took the piss out of everything—it was funny and it was fun! They didn’t take themselves seriously. If you watch A Hard Day’s Night, it’s hysterical! So I kind of wanted to bring a little bit of that energy back into the rock scene, because it had taken itself so far in the other direction! I still feel that way, because it’s at the heart of what I do. Personally, it’s at the heart of what rock ’n’ roll means to me.

RVH: When the Bodyrock album and “Sweet Talk” video came out in 1989, the genre was a stone’s throw away from crashing in North America. Male bands were hanging on, but it wasn’t for too much longer. You kept going and also released Some Girls Do in 1991, which earned you a Juno Award. That had to have a bipolar feeling, receiving acclaim as the market was starting to sag. What do you recall from this period of time?

LA: There was definitely something in the air. I know a lot of classic rock artists like myself have talked about how the advent of grunge killed everyone’s careers. Really, it had to happen, because corporate rock was getting pretty shitty, truthfully. It was exciting when Appetite for Destruction hit, then fast-forward eight, nine years and it had all gotten so derivative. Something had to happen to shake it up, and that something was Nirvana. I remember having a bit of an argument with my manager and my label because I had all the big-hair perm stuff out of my hair; I went and straightened my hair. I was tossing the bustiers because it had become really passé, and they were just panicking, going, “No, no, no! You’ve got to go wear those bustiers again! We need you to have bangs because they’re truly big!” I was so over myself at that point!

So I was really ready to just go with the flow, because I didn’t really have my biggest success until ’89 and ’90. It’s funny, I do a lot of shows where people think I’m older than I am because some of them associate me with the early Eighties, but my great success was in the late Eighties. It was interesting, because that happened, then grunge happened. I was only just catching my breath and going, “What the…that was it? That was my fun?” It was bizarre. We all have choices we can make; you can hang it up and fade into obscurity, or you can go with the flow and consider doing music that helps you stay relevant. A lot of people aren’t aware that I did continue to record. I did an album in ’94, another album in ’95, I had another album in 2000 and then 2004. Albeit, there truly has been a large break between that last one and this one, and that is because I had my kids.

RVH: Going one step further, “Sex With Love” from Some Girls Do in its own way took a stand against the macho male fantasy element that prevailed in Eighties metal and hard rock—along with promoting safe sex. Do you feel people got the message, or was it lost?

LA: The Bodyrock album in Canada was a groundbreaking record. I’m not saying that to sound boastful, but everybody at that time during the Eighties were doing the videos full of fire and brimstone and women with their cleavage hanging out. It was all about testosterone-filled jocks and objectifying women. So I thought, “Okay, let’s do something completely different.” As the follow-up to “Do to My Body,” I’m talking to the director and said, “Let’s do something that’s not fire and brimstone and that’s clean, fresh, and fun. We’ll get a bunch of really hot guys in here and we’ll objectify guys!” All done in a campy, fun way.

They thought that was a great idea, and the cool thing is that video resonated with men and women. So my audience began to change from being more male-based to a very equal balance of men and women at my shows. So the message, I think, at that point was more of a positive message that sort of turned it on its head a bit, turning that whole testosterone thing inside out.

RVH: I can only imagine fans crossing the line, at live shows or otherwise. What kind of freaky incidents have happened to you during your career? Did you ever have to put up with groping or accosting fans? I mean, you did give fair warning with “Hands Off the Merchandise!”

LA: Oh boy, I’ve had a few freakies. I had one stalker in Canada who followed me three-quarters of the way across the country. I mean, it was getting scary being followed all the way through the country to Edmonton, Alberta. I ended up getting ill and having to go to Emergency at the hospital; this was one of the rare times in my career I’d gotten ill. So the guy follows me all the way to the hospital! Okay, this is getting creepy! So, my road crew basically manhandled the guy and put him on a bus and said, “You’re going back home to Ontario!” Then he showed up at the next station! He was absolutely persistent.

So I’ve had that. I had this one time in Edinburgh, Scotland. We managed to get these soccer fans as we got off the bus, and I signed a bunch of autographs. My road manager made the decision that we have got to go to the next town or we’re not going to make it on time, so we’re shutting the bus door, and they swarmed our bus! They were rocking our bus back and forth.

Another time, I think it was somewhere in Belgium, and we were opening for Bon Jovi. We had limited stage space and one thing led to another. I had this custom-made jacket that had all these long fringes on it, and we were out onstage. I had my foot on the monitor and all of a sudden a few of the fans in the front row started grabbing at the fringes. The next thing you know, I was body surfing! We’re total body surfing here! There was this one little asshole in the front row who just thought, “This is my opportunity to grope Lee Aaron inappropriately.” I knew exactly who he was, and I think to this day he still has a boot print on his chest.

RVH: So you’ve split your time performing rock and jazz in recent years. What drew you toward jazz and, in recent years, what has given you more satisfaction performing—rock or jazz?

LA: I actually haven’t been steadily singing jazz for the past couple years. In fact, over the last five or six years, I have been going out more on the summer tours in Canada and more rock festivals, because I’m getting offers to do those. I always knew that I would make another rock record. I just didn’t really know when. I wasn’t about to pressure myself, because the last decade, most of my creative energy has been dedicated to raising my precious little ones. So a couple years ago, I was asked to contribute to a book written by a Canadian author named Sean Kelly—also of the band Crash Kelly—and the two of us worked together on this album.

RVH: That is a super-cute video for “Tom Boy” from Fire and Gasoline. Rockin’ cut, too. To say it’s a new you is an understatement. More like it’s a new tone to your vocals with a hip, contemporary rock kick. Tell me about putting this clip together.

LA: It’s funny. I’ve seen some comments about the video that are super-positive, or I’ve got detractors who just hate it. I can’t allow myself to be fazed by that. That’s the nature of the business when you put yourself out there; you have people who don’t like it. So the girl with the long hair and glasses playing guitar—that’s my daughter! The rest of those little girls are her friends.

The song is written for her. When I had my head down at the piano concentrating deeply with Fire and Gasoline, she goes, “Mother, are you gonna write a song for me for this album?” I was like, “Yeah, yeah, no problem!” So now I have to write a song for my kid! You can’t lie to your children; you have to do what you say you’re going to do. To me, I’ve always felt the greatest songs just write themselves, and sometimes I feel like I shouldn’t even be taking credit, because it’s sort of alive in my brain and I go, “Gee, that’s really cool! I’m not talented enough to have thought that on my own!” Sometimes I really honestly feel that way. Some songs come from a zone in the cosmos or something.

There’s this energy and carefreeness and free-spiritedness that young girls around her age have before they hit the teen years and start caring about what everybody thinks—being self-conscious, being influenced by our culture, which totally objectifies women and is hard-selling a photoshopped type of beauty culture to them. There’s this free-spiritedness to be absolutely comfortable in who they are within their own skin, and I love that. I hate the fact that it’s going to change with my daughter, and I wanted “Tom Boy” to capture that.

In a way, I’m so past caring what anybody thinks, and I’m in the same place right now. As the song evolved, this became a kind of mother-daughter song since we’re both kind of in the same place mentally. It’s also a song for anybody who feels they have to conform to something—a mold that doesn’t fit them. I think we should all have the freedom to not be judged and be exactly authentic to ourselves, and that’s what the song is about. It’s also a song for intelligent women who want to be taken seriously for more than just their looks.

RVH: When you look back at the “Under Your Spell” video from The Lee Aaron Project, what do you see now?

LA: Great song. Fun song. I really enjoyed writing it. In terms of the video, that was shot on one day of my life which became a legacy for me to live down over the next several years. I was a very young girl at the time. When my first manager talked me into doing that, in hindsight, would I have done it again? I’d have to say, absolutely not. I felt like I had to fight for musical credibility for quite a while after that. What can I say? I wouldn’t recommend it. I would fight tooth and nail to keep my daughter out of the same situation.